The most important number in the city’s — and the country’s — homeless policy is the product of a deeply flawed process

Reform is badly needed if future counts are to mean anything

Every year in the third week of January, cities in the United States count their homeless populations.

Or rather, they try to.

Mandated by federal law, the Point In Time (“PIT”) count takes place in the third week of January over one to three nights, depending on the size of the city. Volunteers fan out in cars and on foot in groups of three to four, and count homeless individuals they observe in public spaces, as well as in tents, makeshift shelters, and vehicles. The count is organized according to U.S. Census tracts, which are divided into half to one square mile sub-tracts that are assigned to volunteer teams. The teams consist of a driver/leader, a navigator, and one or two counters. Teams can count as many tracts as they can fit into a three-hour window. In Los Angeles the count is organized by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (“LAHSA”).

A wide range of flaws and confounders

The PIT count is an imperfect science. The threshold question is reliability: With hundreds of teams and thousands of individual volunteers it is difficult if not impossible to establish a truly standardized process. This was my fourth count, and my experiences have been decidedly mixed. I’ve gone twice with friends and twice solo. There’s something to be said for knowing your fellow volunteers ahead of time. While the process sounds straightforward, it requires considerable communication among volunteers. Teams have to reach consensus as to whether any particular individual is homeless, whether that run-down RV parked on the street is occupied, and so forth. They have to make group decisions regarding their personal safety, such as whether to venture down dark alleyways. They have to decide how to approach their tract in the first place. And so on. They will make many of these decisions on the fly in a matter of seconds as they drive down a street counting individuals.

It’s a lot to expect. All of these decisions, of which a dozen or more will arise during any given count, require a degree of trust that’s harder to establish among complete strangers, many of whom are experiencing the count for the first time. It would make for an interesting study into human behavior. Subjectively, I think the counts I did with friends were more thorough than the two I did with strangers. Not to say we didn’t put in our best efforts every time, it’s just that there are limits among strangers that don’t exist among friends. Friends will take chances together that strangers won’t. Friends know how to communicate with one another, know each others’ quirks and limitations. Those kinds of nuances matter, and affect outcomes, but the PIT count process does not account for them.

Recent policy changes exacerbate this weakness. Prior to 2020 volunteers received a 45-minute crash course training before they set out for the count. Since 2020 the training has consisted of an eight-minute online video volunteers are expected to watch on their own before arriving at the counting site. There is no longer on-site training. Many forgo the video and learn on the fly, adding another layer of uncertainty and inconsistency. To address these issues LAHSA would be well-advised to return to in-person training, including a modicum of team building, while encouraging people to volunteer in groups.

There are other practical limitations. Depending on the tract volunteers will count people on major thoroughfares, and even though the count takes place at night drivers can only slow down so much. It can be difficult to count, much less completely and accurately, while rolling down a dark street at 25 or 30 miles per hour. Doubling back is a imperfect fix, as it’s difficult to remember who you counted on the first pass. Volunteers are advised to use common sense and their own discretion when deciding whether to venture into places like alleyways, parks, and beaches, particularly on foot. Last night there were a couple of alleys we simply opted not to check, out of concern for our safety — we were in a “good block, bad block” neighborhood in South L.A. There may well have been people living there, but the balance of considerations left them uncounted.

Finally, the rules of the count imposes other limitations that affect the reliability in other ways. are not allowed to enter structures or approach tents, makeshift dwellings, or RVs. There could be a family of five living in an RV but the count defaults to two adults per RV. Volunteers are not assigned into more remote areas like state parks and open spaces. The beaches are off limits. These restrictions, while understandable and necessary for volunteers’ safety, leave considerable gaps in the overall count. That’s problematic not just in terms of the count’s accuracy, it also may distort our perception of where and how homeless people live in Los Angeles. People living visibly on the streets, in public parks, and in vehicles account for only a portion of the city’s overall homeless population, quite possibly less than a third of the total. For perspective, that would mean that last year’s total count of 46,260 homeless people in the City of Los Angeles could in reality be closer to 140,000.

For example, earlier this week a resident in Venice texted me that she had just witnessed three homeless people emerge from a manhole on Washington Boulevard in Marina del Rey. Anyone who’s ever had occasion to open a manhole knows it’s not the simple task it appears to be: The covers are extremely heavy and require specialized tools to access. In other words, those three people very likely weren’t just randomly exploring around underground.

Likewise, in 2019, a few months before the pandemic, I documented evidence of homeless people living in above ground and subterranean flood channels in Sylmar, Pacoima, and Lakeview Terrace. While exploring one of the channels a group of kids playing in an adjacent backyard shouted at me not to go any further, as homeless people had set booby traps to protect an encampment a little ways up the channel. Similarly, until a cleanup in 2022 around a hundred homeless people dwelt in bunker-like caves they carved into the banks of Balboa Creek in Lake Balboa Park.

Similarly, I and others have documented homeless people living survivalist style in the Santa Monica and San Gabriel Mountains, hunting deer and boar for sustenance. For example, after the September 2019 Saddleridge Fire in the north San Fernando Valley, I contacted a retired Cal Fire arson inspector named Bill Myers. Together we hiked deep into the canyon at the base of the hill where officials said the fire started.

After more than a mile of often bushwhack-style hiking and scrambling we made it to the base of the hill. We discovered the burned out remnants of an elaborate campsite that included numerous cook stoves, a fire pit large enough to roast a deer, and a large amount of garbage. People had carved level spaces into the canyon walls, presumably where they slept. An individual had hung an old hubcap on a tree that he or she apparently had used to hang clothes. Everything was charred. Along with my dogs I climbed to the top of the hill, and at the base of the Southern California Edison tower that was officially blamed for the blaze, one of my dogs dug up a tent, a folding chair, and evidence of yet another encampment in the burn zone.

There was extensive evidence of homeless camping throughout the burn zone of the 2019 Saddleridge Fire. These people were not included in the 2019 count, the consequences of which proved dire.

The PIT count misses all of those cohorts, and likely others. Moreover, there’s the fact that many homeless people are excellent at not being discovered. For many it’s a survival skill. LAHSA does supplement additional data points from non-volunteer sources including demographic surveys and shelter counts, but the volunteer count is the core of the process; also, agglomerating data collected from different sources according to different processes into the same result raises additional methodological concerns.

Finally, federal rules mandate the count be carried out during one of the coldest times of year, late January. In 2022 my friends and I volunteered to count on the Venice Boardwalk. Winter 2022 was historically cold in L.A., to the point that there were partially frozen puddles on the Boardwalk and even on the beach itself. In those conditions many homeless people seek shelter indoors if at all possible, meaning the numbers likely are further distorted.

Despite its limitations, the count is the primary means by which U.S. cities attempt to get a handle on their homeless populations. The results have far-reaching implications, most importantly on budgeting decisions: The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (“LAHSA”) uses the numbers to make funding allocations.

This year the count faced the same problems, along with some new ones

Before delving into everything that went wrong this year, there were bright spots. At the staging site at Holman United Methodist Church in the West Adams neighborhood of South L.A., where I volunteered on Thursday night, the staff and organizers were on their game. They were knowledgeable, well-prepared, cheerful, and helpful (with the exception of tech support — more on that in a moment). Despite the absence of formal on-site training they answered volunteers’ questions and generally did a yeoman’s job. To boot, they brought homemade soup and chili in big chafing dishes, bags of Subway sandwiches, homemade chocolate chip cookies, and all manner of snacks. Pardoning the pun, the community room in the church smelled downright heavenly.

They also supplied the volunteer counters with hygiene kits, water, and fresh fruit to hand out to homeless folks they might encounter (technically this was against the rules, as volunteers are admonished not to disturb or interact with homeless people during the count. However, in my estimation it was a justifiable bending of the rules for a good purpose).

Their efforts worked, as the volunteers fanned out into the community with a sense of purpose, even enthusiasm, that was lacking in my previous experiences. For example, the first year I volunteered, in 2018, the LAHSA organizers spent several minutes arguing with each other about the proper way to count makeshift dwellings.

I was there with John McKinney, a Los Angeles prosecutor and leading candidate for District Attorney (disclosure: I work with the campaign). He was there to get a boots-on-the-ground look at the process that is central to the City and County of Los Angeles’s homelessness efforts. A third member of our team dropped out due to illness, so we were assigned two other folks, making us a hybrid team of friends and strangers. We were joined by a woman named Robin who works in systems design, and a doctor named Sarah. John drove and served as lead, Robin navigated, Sarah and I counted, and I recorded the count into the app. We were a good team with good rapport, and did a thorough job.

We were assigned sub-tract 219300, bordered by Crenshaw Boulevard and 10th Street on the west and east, and by Adams Boulevard and Exposition Boulevard to the north and south. The actual count took about 90 minutes, and we ended up with a total of 17 individuals, one youth (18-24), along with two cars, five vans, two RVs, two tents, and 10 makeshift dwellings.

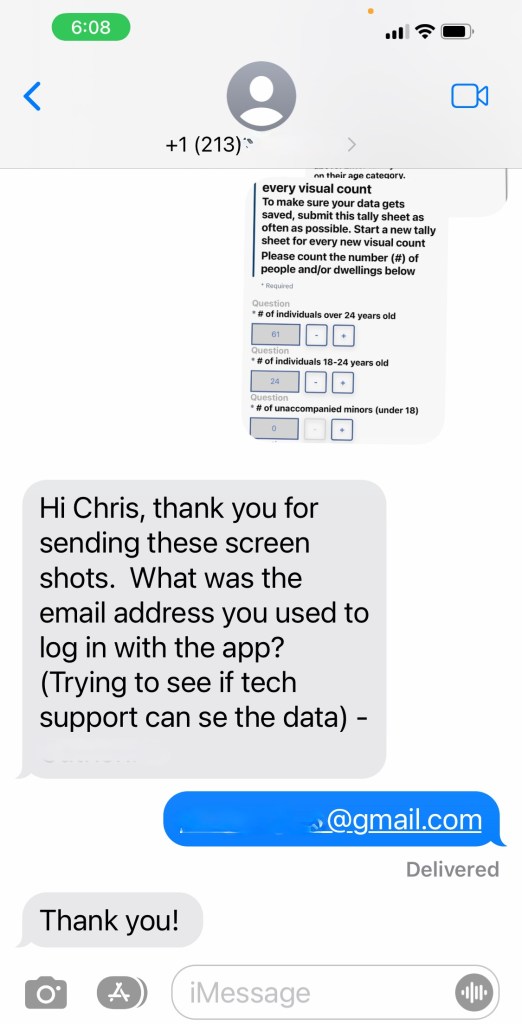

At least, I think we did. After years of relying on clipboards and pens and paper, for the first time in 2022 LAHSA introduced a smartphone app for volunteers to record their counts. Or rather, that was the theory. The app, developed by a small tech firm called Akido, was poorly designed and difficult to use. It had extremely small toggle buttons and a user interface that appeared to have been designed by M.C. Escher. For a tech-limited individual with big thumbs such as myself, these shortcomings made the app exceptionally challenging for what otherwise is a straightforward task. A clipboard and pen would have been far superior. Worst of all, when my friends and I attempted to upload the data, the entire app crashed. Fortunately I had taken screen shots, which I texted to the personal cell phone of one of the LASHA workers. Talk about a broken process with zero statistical credibility.

That year in our half square mile sub-tract on the Venice Boardwalk we counted a staggering 279 homeless people. However, thanks to the technical snafus, when LAHSA reported the results of the count five months later they reported zero people in the sub-tract. Zero. I wrote about the experience, and my friends and I worked with David Goldstein at CBS Investigates to expose the story.

As a result of our efforts LAHSA fired Akido and hired a different company. This time they went with Esri, a leading geographic information system (“GIS”) developer that reported $1.1 billion in revenue in 2022, with 40% of the domestic GIS market. LAHSA brought in the big guns.

At first the new app, called QuickCapture, looked promising. The UI was a vast improvement over the previous app, with big, easy to read icons and a straightforward layout. An automated voice confirms every time a user taps an icon with an audible “adult individual,” “car,” “tent,” and so on. So far so good.

It was when we got back to the staging site and tried to upload our numbers that the problems started. The biggest one was the app’s location feature. It appears to designed around the “general vicinity” theory of GPS based navigation. It only recorded about a third of the count in the correct sub-tract, and sprinkled the rest among five other adjoining ones. Worse, the numbers kept changing. At one point when I pulled up the screen the app reported that we’d counted 19 individual adult homeless people in our assigned sub-tract – except the number literally vanished a second later and reverted to zero.

The LAHSA employees were blindsided. There were two IT staffers, one of whom unfortunately gave off the cliche “I know about computer stuff therefore I’m smarter than everyone in this room” vibe. His assistant was more helpful but was also marginalized. At no point was there a general announcement as to how volunteers should try to work around the failed app.

Of course, everyone’s app was doing the same things, meaning the entire exercise was worse than meaningless from a data integrity standpoint. After about 45 minutes of troubleshooting (while volunteers stood around chatting, eating cold chili, and killing time) the LAHSA officials gave up. They instructed people to write their counts on their paper maps and turn them in. We stopped even trying to upload the data from the app.

A homeless count is not the time to make it up as you go along

There are so many problems with this ad hoc solution it’s hard to know where to start. First and most obviously, having switched to a smartphone app based process two years ago LAHSA is ill-equipped to revert to processing thousands of physical paper maps and pen and ink chits. Several exasperated volunteers gave up and left altogether (it was after midnight at this point). Soup and chili only buys so much goodwill.

The biggest issue, though, was the unreliability of the numbers, which as I said literally changed before our eyes. I spoke with several other volunteers – including a woman who works for the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, which is LAHSA’s big boss. Everyone was experiencing the same issues, up to and including disappearing numbers. Dan Flaming, Director of the Economic Roundtable, which over the years has conducted extensive analyses into the PIT count’s data integrity and processes, reported to me that similar issues plagued the count where he volunteered, in the downtown Arts District.

Based on last night’s experience, and in light of our experiences in 2022, I have an extremely low degree of confidence in last night’s process. Given those experiences and the importance of the count, and given that LAHSA relies on the time and goodwill of volunteers, who in many cases risk their personal safety in the process of performing a public service, one would think this government agency, with its $845 million 2023 budget, would have nailed what amounts to a simple tallying app. It’s a matter of a half dozen icons and a counting feature. That’s it. We aren’t trying to land a rover on Mars here. Yet the agency, whose current Director makes nearly half a million dollars a year, couldn’t pull it off.

Extrapolation is a delicate art, and it’s important to be cautious before drawing too many broad conclusions. Still, the fact that the largest homeless services agency in the country, with some 800 well-paid, unionized employees, cannot accomplish one of the foundational processes that is part of its very raison d’etre, sheds light on the overall failures of our city’s and county’s efforts to address homelessness. The fact that identical problems crop up year after year is cause for more doubt. The fact that LAHSA spends millions to address them, only to make them worse, is cause for a complete lack of confidence.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but if they cannot master arithmetic, how on earth can they be trusted with the far more complex challenges of the crisis itself? Last year, on top of the app crash and other issues, LAHSA took six full months to report the count results. Six months, to do basic addition.

Put another way, what the hell are Angelenos paying all this money for? So LAHSA can make it up as they go along?

No wonder some L.A. officials want to shut down the agency altogether. In fact, that would be an excellent place to start.