City and County agencies are proposing 19th century solutions to 21st century challenges

Never, ever gonna happen. At least Metro’s rendering is accurate, showing an empty train and an empty station.

In today’s Los Angeles Times, someone called Roy Sosa, who is the Chief Planning Officer at the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (“Metro”) engaged in a bit of magical thinking. His op-ed ruminated on the city’s alleged need for a heavy rail subway through the Sepulveda Pass, beneath the 405 freeway. This project has long been one of Metro’s biggest unicorns, intended to connect the southern San Fernando Valley with the north Westside.

I’ll start with something Sosa gets right: During commute times, and often even at off peak times, the 405 is a bloody nightmare. It can easily take 90 minutes just to get from Santa Monica to, say, Lake Balboa Park, a distance of around 15 miles. For the mathematically inclined, that works out to an average of just under 10 miles per hour, on a freeway intended for traffic traveling at 65 miles per hour.

Just what L.A. needs, another public spending boondoggle

Metro proposes to tackle the challenge with 19th century technology. In an era when cities including Atlanta, Pittsburgh and L.A. County’s own Beverly Hills are successfully deploying AI and machine learning to help alleviate traffic congestion for a few hundred thousand or a few million dollars, Metro wants to spend $24.7 billion of the people’s money to build a 15 mile subway route with a grand total of eight stops. Of course, everyone knows that the original price tag amounts to little more than a sales pitch. Assuming that, like nearly all large public works projects in California over the last three decades, the price doubles, we’re talking about a $50 billion train, or $3.3 billion per mile. That works out to $625,000 per foot.

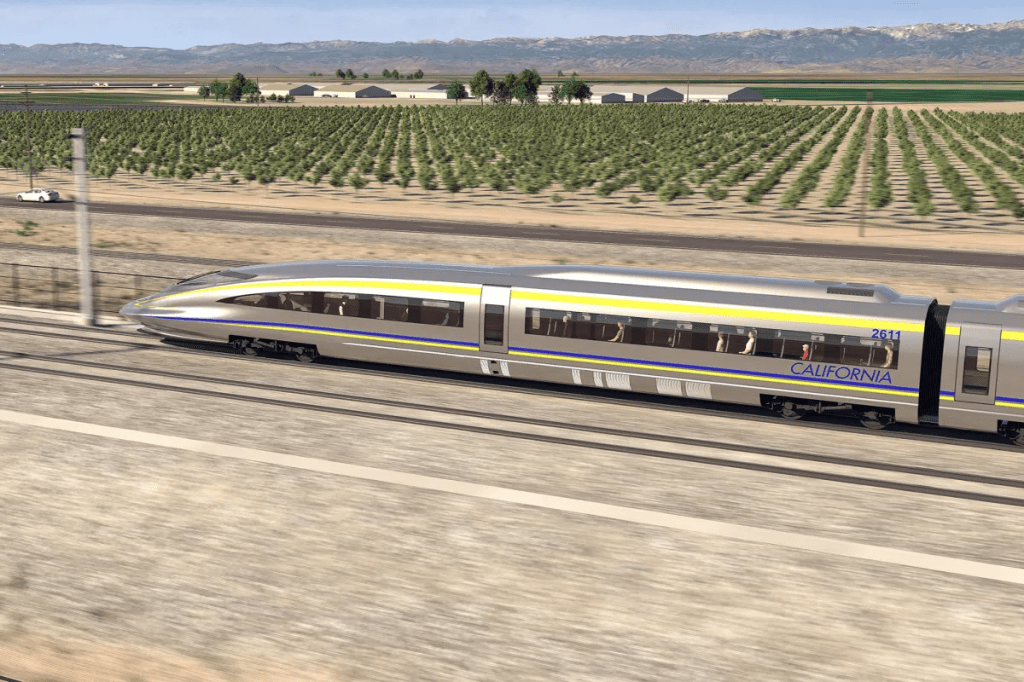

For comparison, the original California bullet train proposal was supposed to cost $30 billion and cover 400 miles. Current plans call for a 171 initial operating segment between Merced and Bakersfield (aka, the middle of freaking nowhere) for a cool $33 billion. That is, less than half the original planned route for more than the entire original project estimate. It’s safe to assume any Sepulveda Pass subway will generate the same kinds of overruns.

Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so?

Indeed, the estimated cost of the subway to nowhere already has quadrupled from $6 billion in 2016 to more than $24 billion today. According to Metro, “A shorter, or initial operating segment, more direct alignment and fewer stations could reduce costs.” Sound familiar?

Even if it does get built, sometime in the next 15 to 20 years, it will serve virtually no one and do next to nothing to alleviate congestion on the 405. This is where ideology — transit good, cars evil — runs headlong into physical reality.

The likelihood that an Angeleno will be able to get everywhere she needs to be — work, school, social engagements, recreation, exercise, entertainment, medical appointments, etc. — using mass transit is, in a word, delusional. The idea that a family with two young children who attend different schools, have different extracurricular and sports commitments and different circles of friends can reach all those commitments on transit is farcical.

A small fraction of L.A. County residents do rely on transit, but even they also get rides from car-owning family members, friends, and neighbors for a good portion of their trips. As a comprehensive 2017 research paper from the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies — no big opponent of mass transit — observed, “compared to Americans at large, the poor use transit more but like it less. The typical low-income rider wants to graduate to automobiles, while the typical driver might view transit positively but have little interest in using it.”

Translation: The commuter stuck in 405 gridlock hell may notice the new subway station and think, “Cool.” But he’s never going to ride it. What’s more, the fastest growing cohort of car buyers over the last decade has been first generation immigrants. A $50 billion subway through the canyon isn’t going to move those needles one millimeter.

Some of Sosa’s assertions bleed from the delusional into the downright deceitful. He claims, “The forecasted reductions in vehicle miles traveled are astronomical at 775,100 miles each day. For comparison, the moon is 238,900 miles away.”

According to Metro’s own numbers, approximately 280,000 vehicles travel through the Sepulveda Pass on a typical weekday. A substantial majority are single drivers. That translates to 4.2 million vehicle miles along the 15 mile segment. In other words, even if Metro’s fanciful ridership estimates come to fruition, the $50 billion subway will reduce traffic by 18%. That’s not nothing, but it’s hardly a game changer. And again, it’s all but certain that actual ridership will be a small percentage of the agency’s notoriously inflated ridership estimates.

This is brutal, but a subway isn’t the solution.

(As an aside, comparing estimated vehicle miles saved to a one way trip to the moon is like comparing the number of marbles in a glass jar to the number of mallards in the nearby park).

There’s another tell in Sosa’s argument. He writes, “But the investment is justified. Transit is a vital public infrastructure that provides the mobility necessary for thousands of Southern Californians to earn a living, further their education and access healthcare.”

“Thousands of Southern Californians.” Not hundreds of thousands, not millions. There are as close as makes no difference 4 million people in the City of Los Angeles and 10 million in the county. A handful of thousands use public transit.

In 2022, driving alone (67.4%), carpooling (10.1%) and working from home (15.7%)accounted for 93% of work access. Just 2.5% took transit, which works out to around 100,000 people in the city and 250,000 countywide. A substantial majority of those riders are students and low income people, both cohorts that aspire to car ownership. Indeed, over the last 40 years, even as L.A. invested tens of billions in new transit, particularly light rail lines, the percentage of people who commute via car actually increased by nearly 10%. Ridership on mass transit was in decline throughout California for decades. Between 2020 and 2023 the pandemic crashed what little ridership there was.

Mass transit for all a few

There’s also the question of the inherent discrimination in public transit. Buses, subways and light rail are of no use to working people like carpenters, contractors, plumbers, electricians, landscapers, mechanics, gardeners, home caregivers and other cohorts who haul equipment and materials to jobsites, often more than one jobsite per day. Despite accessibility requirements they are inconvenient for people with disabilities. In recent years transit has proven dangerous to single riders, particularly women and particularly at night.

This can, like, totally fit on a bus….

The latter reality reveals another aspect of Metro’s fundamentally misguided ways. As crime spiked on transit over the last few years, the agency severed ties with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, which had historically provided security and law enforcement services to the system. At the same time, the agency spent millions to install bulletproof plastic barriers around drivers’ seats on its vehicles and trains. Riders, in contrast, were left to fend for themselves.

There are solutions to L.A.’s traffic, starting with smart traffic controls and AI powered monitoring that can be deployed in weeks and months rather than years, and for a fraction of what Metro wants to spend on a single, short subway line. Traffic lanes can be restored on main thoroughfares that have been “road dieted” to accommodate the 0.5% of (overwhelmingly young, fit, white male) Angelenos who chose to get around on bicycles. Employers can be encouraged to think creatively about work hours, and to adopt remote work to the greatest reasonable extent without impacting productivity.

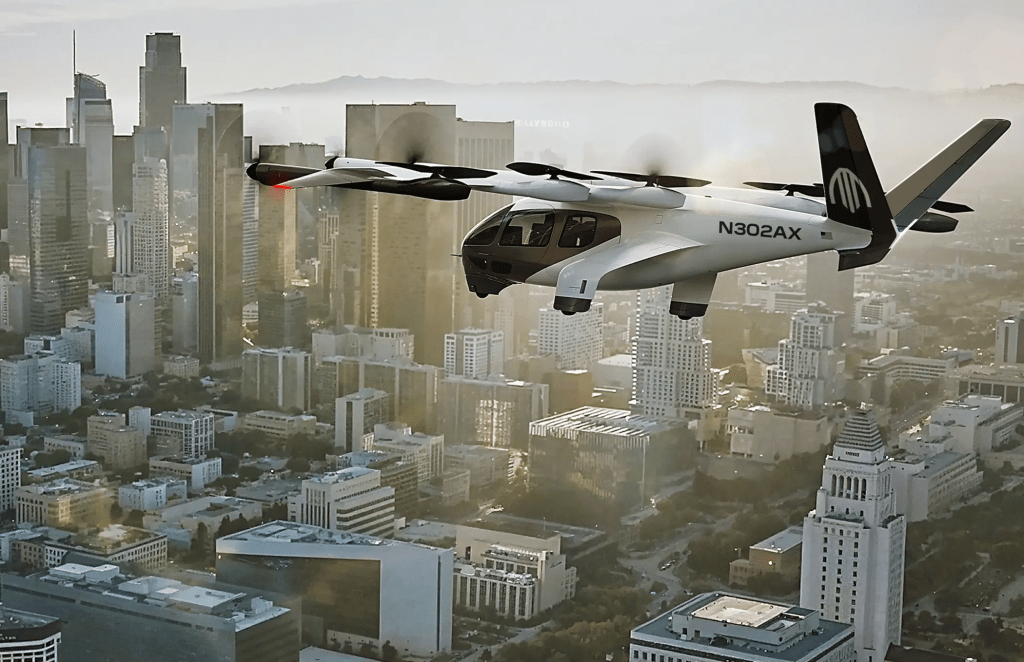

Moreover, a whole new generation of transportation is on the immediate horizon. More than a dozen startups are working on autonomous vertical take off and landing air taxis and personal airborne vehicles that don’t require a pilot’s license. Drone deliveries will soon cut the number of delivery vehicles on the roads significantly.

The future is vertical.

In short, the future is in the air, not underground. Metro should take that $50 billion and invest it in advanced technologies that serve the entire region, from mountains to coastline and all points in between, not a single 15 mile subway to nowhere.