The flaws with “abundance” theory

Part I of a series

Ever since Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson published their book, Abundance, in February, the word has been on the lips of liberal policymakers, pundits, politicians and analysts. In our short attention span theater era (shout out, Gen X), it became an instant nostrum, a catchword that simultaneously purports to explain what ails the modern U.S. economy and society and offer solutions. For all intents and purposes Klein and Thompson have written the political platform for moderate and conservative Democrats. Indeed, Abundance reads more like an agenda than a book. It’s heavy on soundbites and light on research and detail.

Before offering criticism, let’s look at a few of the things Klein and Thompson get right. They correctly point out that modern liberal governance is tangled in too much process, risk-aversion and regulatory and procedural hurdles that thwart forward progress. Decision-making is often opaque and tenebrous even to the decision-makers. Bureaucracies have come to exist for the sake of existing, self-perpetuating public employment machines for people who otherwise would have to find real jobs.

They call it “Everything Bagel Liberalism,” which is unfair to everything bagels, which are delicious. But their diagnosis is accurate as far as it goes: Modern government, particularly of the liberal sort, tries to do everything and ends up doing almost nothing other than spending money.

They get those basics mostly right. Unfortunately, that’s about as far as it goes. Much of the rest of the book amounts to economic illiteracy and political naiveté. When all is said and done it amounts to magical thinking.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss

The biggest of the many problems with Abundance and the associated movement — and the problems are myriad — is that the prescription Klein and Thompson offer amounts to more of the same. While acknowledging the failures of the modern, Kafkaesque. bureaucratic liberal experiment, they turn on their heels and argue that the remedy is more bureaucracy. The only difference is that they envision bureaucracies of efficiency, a contradiction in terms if ever there was one.

They write, for example, “Whether government is bigger or smaller is the wrong question. What it needs to be is better. It needs to justify itself not through the rules it follows but through the outcomes it delivers.”

No one would argue with this statement in principle. The problem is that it amounts to an empty tautology: Government is bad, so it should be better. Klein and Thompson offer frustratingly few specifics as to how cities and states might go about accomplishing this goal. They vaguely suggest that government needs to hire more and better experts, people who can “get things done.”

In an interview with PBS promoting the book, Klein remarked, “Government needs the capacity to deliver — the people who can build things, not just regulate them.”

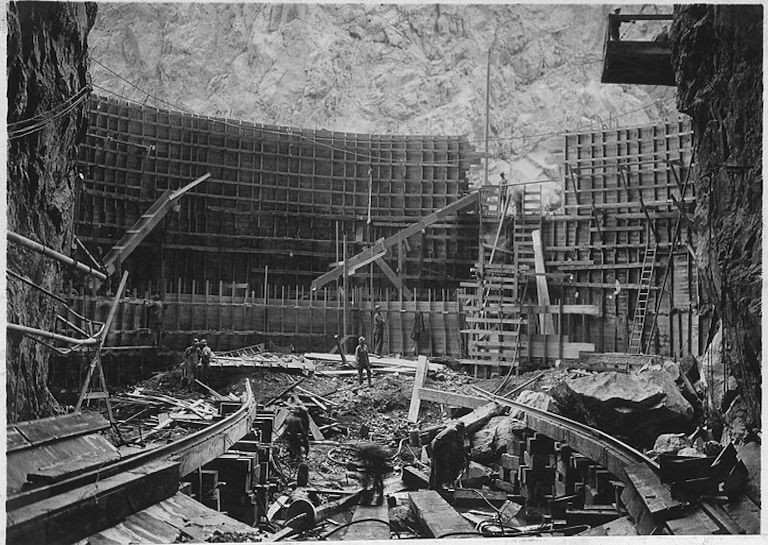

In addition to its vagueness, that notion is hopelessly outdated. The authors pine for the heady days of the California Aqueduct, the Hoover Dam and the Interstate Highway System. But this is a different era. Aside from a bridge here, a subway extension there, the days of large scale government-run infrastructure projects are largely over. Government has transitioned from a builder to a regulator, maintainer and servicer. The people who know how to build, say, a nuclear power plant or a new rail line are almost entirely within the private sector.

A bygone era: The Hoover Damn under construction.

That goes a long way toward explaining why, when government does try to execute large scale projects, they invariably end up years or even decades behind schedule and billions over budget, if they get built at all. When any large entity, be it public or private, loses expertise it’s almost impossible to get it back.

For example, after the production run for the Air Force’s F-22 Raptor air superiority fighter ended, military leadership realized we needed many more than the 187 that were built. It was too late. Lockheed Martin had shut down and repurposed the factory where final assembly took place, the engineers had gone on to other projects and suppliers were fulfilling new contracts. In a very real way the company had “forgotten” how to build the airplane.

Similarly, outside of a few specific areas like water and power delivery, water treatment and public transit, government has “forgotten” how to build large-scale infrastructure projects. At the same time, government never learned how to build modern infrastructure in the first place, things like data centers, fiber optic backbone networks, 5G wireless networks, cloud computing platforms, fulfillment centers, solar and wind farms and so on, which are entirely the domain of private enterprise.

In short, Klein’s and Thompson’s prescription is misguided. Government doesn’t need to re-learn how to build things, it needs to get out of the way of the entities and individuals that build in the modern era. The United States doesn’t need better government, it needs less government.

Consider the example of the federal Department of Education. Jimmy Carter established it in 1977 in fulfillment of a campaign promise (contrary to conservative talking points, while the teachers’ unions were strongly supportive of the new agency — because it represented a centralized source of control — it was not purely a sop to them). No one in their right mind would argue that today, nearly half a century later, education is in better shape than it was back then. That’s not a coincidence, that’s the modern public bureaucracy in action.

The compounding problem: The Paradox of Expertise

Even in areas in which government does still design and build things, like transit systems, no amount of magical thinking can change a fundamental reality: Bureaucracies, especially of the governmental sort, eventually reach a point at which they experience what we might call the Paradox of Expertise.

Consider the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (“Metro”). The agency has nearly 12,000 employees and a budget of $9.3 billion. For perspective, the 2025 budget for the entire state of Rhode Island is $7.3 billion.

Within the bowels of Metro toil experts on scores of topics, from planning, design and operations to capital projects, maintenance, environmental compliance, inter-city coordination, funding and so forth. And within those areas of expertise are sub-experts on bus routes, bus rapid transit routes, light rail routes and Metrolink routes, as well as sub-sub-experts on subjects like roadway design, paving, lane striping, lighting, electrification, accessibility, emissions, bike lanes, bikeshare, vanpools, micro mobility — on and on, far into the night.

The first consequence of the Paradox of Expertise is that Metro as an organization and system is so complex that no one individual, nor even a board of directors, can possibly understand the sum of all its parts. In other words, no one in the world knows how L.A. Metro works.

Tom Rubin is one of the country’s leading transportation experts and the former Chief Financial Officer of Metro’s predecessor, the Southern California Rapid Transit District. He points out a crucial weakness: Planners and engineers occupy different worlds, speak different languages and tend to view each other with suspicion. The people who plan new or modified bus and light rail routes rarely consult with the people responsible for designing and building them.

The result is chaos: Bus routes that make no logical sense, light rail lines that cannibalize the few efficient bus routes that did exist, routes served by vehicles that are many times larger than ridership requires, new bicycle lanes that snarl traffic while attracting virtually no riders, overall inefficiency and enormous wastes of taxpayer money.

The second, related consequence of the Paradox of Expertise is siloization. Every expert, sub-expert and sub-sub-expert is consumed with their particular area of expertise. In this context, success is measured not in tangible outcomes but in departmental growth and expansion. This is what’s known as the budget-maximizing model, first theorized by the economist William Niskanen in the late 1960s. According to the model, bureaucracies incentivize managers not to coordinate with other managers to achieve good outcomes, but to compete with them for scarce dollars and resources. Rational bureaucratic managers seek to always and forever increase their budgets in order to increase their own power. This also helps explain the mutual suspicion: They’re all after the same pot of money.

The Paradox of Expertise and the budget-maximizing model explain why bureaucracies with the best of intentions grind down into immobility, spending billions of dollars with nothing to show for it. Exhibit A is California’s disastrous High Speed Rail Authority (“HSRA”), which has spent some $14 billion over 17 years without laying a single foot of track. Mind you, the agency’s original promise in 2008 was to complete an initial 400 mile operating segment between San Francisco and Los Angeles for $33 billion by 2020.

Current plans call for a radically scaled back 179 mile initial operating segment between Merced and Bakersfield, aka the middle of nowhere. The cost is estimated to be — wait for it — around $33 billion, with service estimated to commence in 2032 or 2033, a quarter century after voters approved the project. That’s if everything goes perfectly from here forward, which is as likely as you or I flapping our arms and flying to Madagascar.

Whaddya expect for a lousy $14 billion?

Klein and Thompson (remember them?) refer to the failure of California’s high-speed-rail adventure as the “poster child” of how overly burdensome regulations, environmental reviews, zoning laws, lawsuits and procedural complexity have made it extremely difficult to build even when there’s public support and funding. What they fail to grasp is that those barriers to success are baked into the bureaucracies responsible for bringing the project to fruition. They aren’t externalities that can be controlled with better management. Who do the authors think is responsible for those regulations, reviews and laws?

L.A. Metro and the California HSRA are but two of nearly endless examples of government impotence, the primary symptom of the loss of expertise and practical know-how over time, compounded by the Paradox of Expertise and the budget-maximizing model.

Government can never be reformed to produce “abundance,” so it needs to get out of the way

Rather than double, triple and quadruple down on the failures of government bureaucracies, a positive agenda should focus not on delivering abundance but on creating prosperity. Abundance is a supply-side solution, prosperity focuses on demand. In human terms, abundance is a matter of reforming unreformable bureaucracies. Prosperity is about increasing individual potential and flourishing, in no small part by getting government out of the way.

The frustrating thing is, Democrats used to accept this. There were “Reagan Democrats” who disagreed with the Gipper on social and foreign policy issues but broadly agreed with his argument that government all too often was the problem. In 1996 Bill Clinton declared “the era of big government is over.” He tasked Al Gore with finding ways to reign in the regulatory state.

How can we do this? We start by getting government out of the way. Not in a frenetic, DOGE-y way but strategically. Where are the biggest bureaucratic bottlenecks? Where can budgets be cut without sacrificing essential services? Where is the bloat? In contrast, which agencies need more funding (fire departments, parks)?

Again, we can look at L.A. Metro. An easy (relatively speaking) place to start would be to identify overserved routes, that is, routes with paltry ridership that are served by full size or articulated buses. Save money by replacing those vehicles with smaller jitneys or even on-demand point-to-point service. On other routes the agency could partner with private ride share companies like Lyft or Uber.

Almost entirely unnecessary.

Next, perform a top-to-bottom review of all 300 routes in the system. Which can be re-routed to promote efficiency? Which can be eliminated or merged? How can the average number of transfers be reduced? And so forth.

Perform efficiency evaluations at every major city, county and state agency. Make people justify their jobs. Bring in third party consultants who know how to ruthlessly cut bloat. This isn’t reforming government, it’s reducing it. It’s putting it back in its place of providing essential services and otherwise getting out of the way.

Ultimately, the goal should be to reduce government budgets at every level, reduce the state’s onerous ecosystem of taxes, fees, assessments, fines and other extractions, and return as much to the people as possible. No civilization in history has ever taxed its way to prosperity.

Reality check

As a concluding note to this first part of the series, it’s important to state the obvious: Reducing government and making it more efficient at what it should do is a herculean task, especially in a place like California with its overlapping interests of politicians, donors, organized labor (particularly in the public sector), business interests and deeply entrenched public agencies.

Nevertheless, there’s reason for hope. Outside of extreme circles like the Democratic Socialists of America there is increasingly bipartisan recognition that government has lost its way. This suggests an opening for moderates from both sides to chart a unifying course toward efficiency that ultimately will unlock prosperity.

In the next installment we’ll explore how a return to local control and local democracy can enhance accountability and help drive prosperity, and why prosperity is a better goal than abundance.

Like what you’re reading? Please consider supporting independent journalism with a one-time or ongoing contribution to the all aspect report.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you! Donations securely processed via Stripe.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly