In its 29 years as a federal penitentiary, no one is known to have escaped Alcatraz Island. Between five and ten inmates drowned during escape attempts (the larger number reflects an attempt by five inmates in 1962 who remain listed as missing and presumed dead). It’s 1.25 miles from the island to the nearest mainland shore in San Francisco. It’s among the most treacherous 1.25 miles of ocean in the world. San Francisco Bay is notoriously frigid, and its currents are intense and unpredictable. The narrow mouth of the Golden Gate creates a marine Venturi effect, accelerating and chopping up the massive tidal flows from the Pacific Ocean.

These days there are several open water swimming competitions to or from Alcatraz. However, the races are closely monitored by scores of lifeguards who line the routes in kayaks and boats, as well as Coast Guard personnel. Suffice it to say, John and Clarence Anglin had no such support.

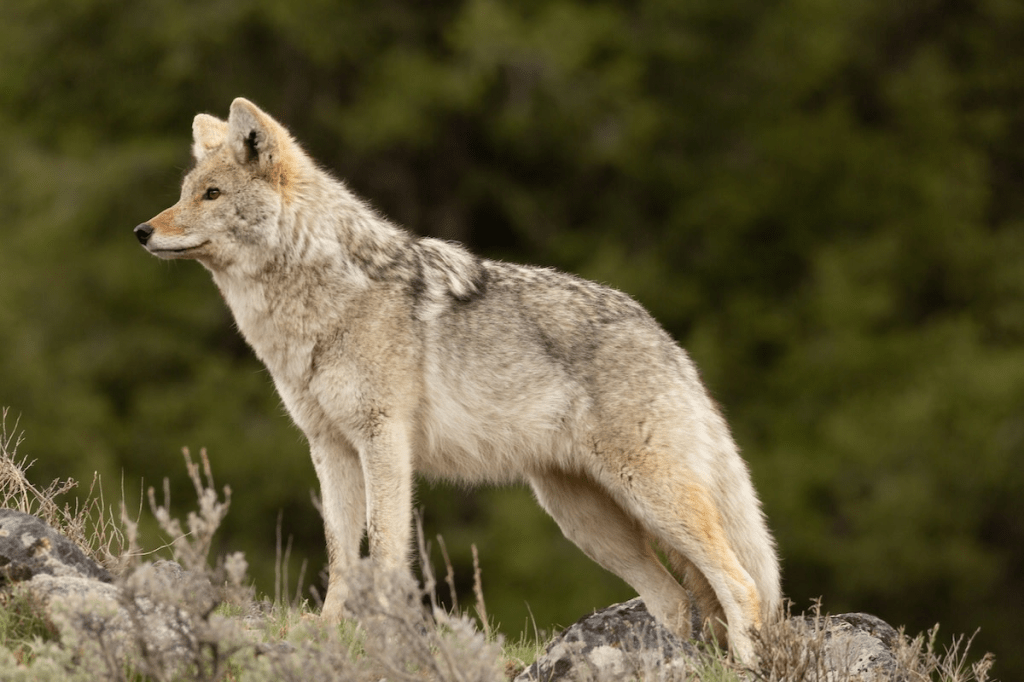

Nor did a supremely intrepid coyote. Two weeks ago, a courageous canis latrans accomplished the feat in reverse, swimming the 1.25 miles from shore to island. The last part of his journey was captured on video by an anonymous tourist. In stills published in local media, his head is visible above the churning Bay waters. If that’s not determination, I don’t know what is.

Bad ass, coyote, bad ass.

His post-swim survival seemed in doubt for a few days, and at least one report erroneously claimed he had died. On Tuesday, Janet Kessler, a self-taught naturalist and coyote expert who lives in San Francisco and has documented the specie’s population in the city for years, shared concerns about the animal’s odds of survival with the San Francisco Standard. She told the outlet that “the swim would have drained the coyote’s body heat and energy reserves … leaving it in desperate need of food, water, and warmth on an island with limited resources.”

I am happy to report that he’s not only alive and well, but according to recent reports he is living his best life. He’s enjoying his own personal one-canine buffet of island sea birds, growing “noticeably fatter” in the two weeks since his arrival, according to an employee with Alcatraz City Cruises. With great risk comes great reward.

Kessler believes the coyote made the journey as a result of population pressure. Coyotes are highly territorial, living in closely bonded family groups. They actively chase away intruders and interlopers, whether they be of the coyote, domestic dog or human variety. Kessler has documented 20 coyote families in San Francisco, each with unique personalities and relationships. When young coyotes reach maturity, at between two and three years old, they “disperse,” leaving their families to establish their own territory and seek mates. The Alcatraz coyote appears to be around that age, suggesting he took a unique approach to his own disbursement.

Contrary to popular belief, coyotes are not pack animals like their wolf cousins. And while lone coyotes are uncommon, they’re not unheard of. Coyotes are known for what biologists call “fission/fusion” behavior, able to switch between solitary and group living depending on available resources. It’s possible that, thanks to Alcatraz’s abundance of sea birds and mice, the coyote will be content to swap a mate for a guaranteed diet.

A coyote smiles at my dogs after chowing down on a ground squirrel on the West L.A. V.A. campus.

I love this story in part because it’s easy to imagine the coyote’s thought process. Coyotes are supremely intelligent. I imagine him standing on the shore and thinking, “Let’s see. Behind me is a big, noisy city with a lot of coyotes competing for limited resources. It can be extremely stressful, this city life. Also, Frisco drivers suck and kill about 40 of us every year. Over there, on the other hand, is an island teeming with abundant prey, no cars, no noise, no competition and not too many humans. Fuck it, let’s do this thing.”

Incidentally, you should definitely check out Kessler’s Instagram. Her photos and videos of San Francisco’s coyotes are stunning.

I’ve loved coyotes all my life. They are endlessly survivable and adaptable, cunning, loyal and playful. Growing up in a canyon in the Santa Monica Mountains, I would often hear coyotes yelping and howling as I lay in bed at night. Some people find the sound unnerving or annoying. To me they were hauntingly beautiful lullabies. Coyotes were frequent visitors in our neighborhood, and from time to time in our yard. I see them occasionally on hikes around L.A. I sometimes joke with friends that I was half raised by coyotes, as a free range Gen X kid who roamed the hills and frequently encountered them as friends.

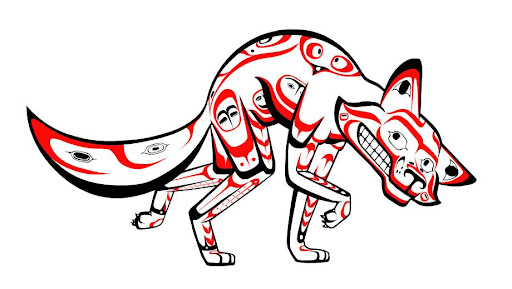

The coyote is a central character in the mythologies of native American tribes throughout the west, southwest and plains. He’s often portrayed as a trickster who uses his cunning to fool humans and other species. He’s also a creator, with some stories crediting him with creating or helping to create the Earth itself. In other stories he helps people out of trouble. Occasionally he’s an evildoer, but most of the time he’s a friendly, mischievous character.

The Alcatraz coyote adds a new chapter to these stories, and to the story of humans’ relationship with these wonderful, amazing creatures. The National Park Service is monitoring him. I, for one, hope they leave him be. He’s earned his feast, and his place in California lore.

Long live the Alcatraz coyote!