It’s one of the most famous phrases in U.S. history. At the end of his first inaugural address, President Abraham Lincoln implored Americans both north and south that “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

The bulk of Lincoln’s address consisted of rational, legalistic arguments that persuaded no one. He delivered run-on sentences appropriate for a courtroom judge and jury, not a restive people on the brink of fratricide. He contradicted his core thesis, at one point declaring, “This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.” Of course, the Confederacy’s entire purpose was to dismember and overthrow the Union.

In many ways, the speech was quintessentially American. At an hour of maximum danger it was conceived, composed, and delivered with the lingering hope that our better angels would prevail. It was hopeful almost to the point of delusion. It assumed that rational argumentation could prevail over human passions.

Lincoln, of course, harbored no delusions. By March 4, 1861, the day he delivered his address, seven states had seceded. The Confederate Army was up to half a million men, with more mustering every week. Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy or to so much as meet with its representatives. His administration warned European powers, particularly England and France, that recognizing the Confederacy would provoke war (that was quite the bluff, of course; there was no possible way the United States could have fought two wars at the same time).

And yet. Six weeks before those first shots, Lincoln held out hope, or at least pretended to. When you’re President of the United States, that’s a distinction without difference.

Over this long weekend I’ve been thinking a lot about Lincoln’s words. I’ve also thought about another speech he delivered, under quite different circumstances, two and a half years later at the Gettysburg Battlefield. He spoke of our better angels again, albeit with different words. “We here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The United States of America is a deeply flawed nation. To paraphrase Governor Willie Stark in Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men — a less salubrious meditation on the nature of U.S. history and political power — we were conceived in sin and born in corruption, and we will pass from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud. Then again, this much is true of every nation in human history. Nations are, after all, products of moral compromise.

At the same time, what other nation has ever sought out the better angels of their nature? What other nation has been so naive to even utter the phrase, much less on the brink of total war? What other nation was conceived not in sin alone, but in the parallax of sin by hope?

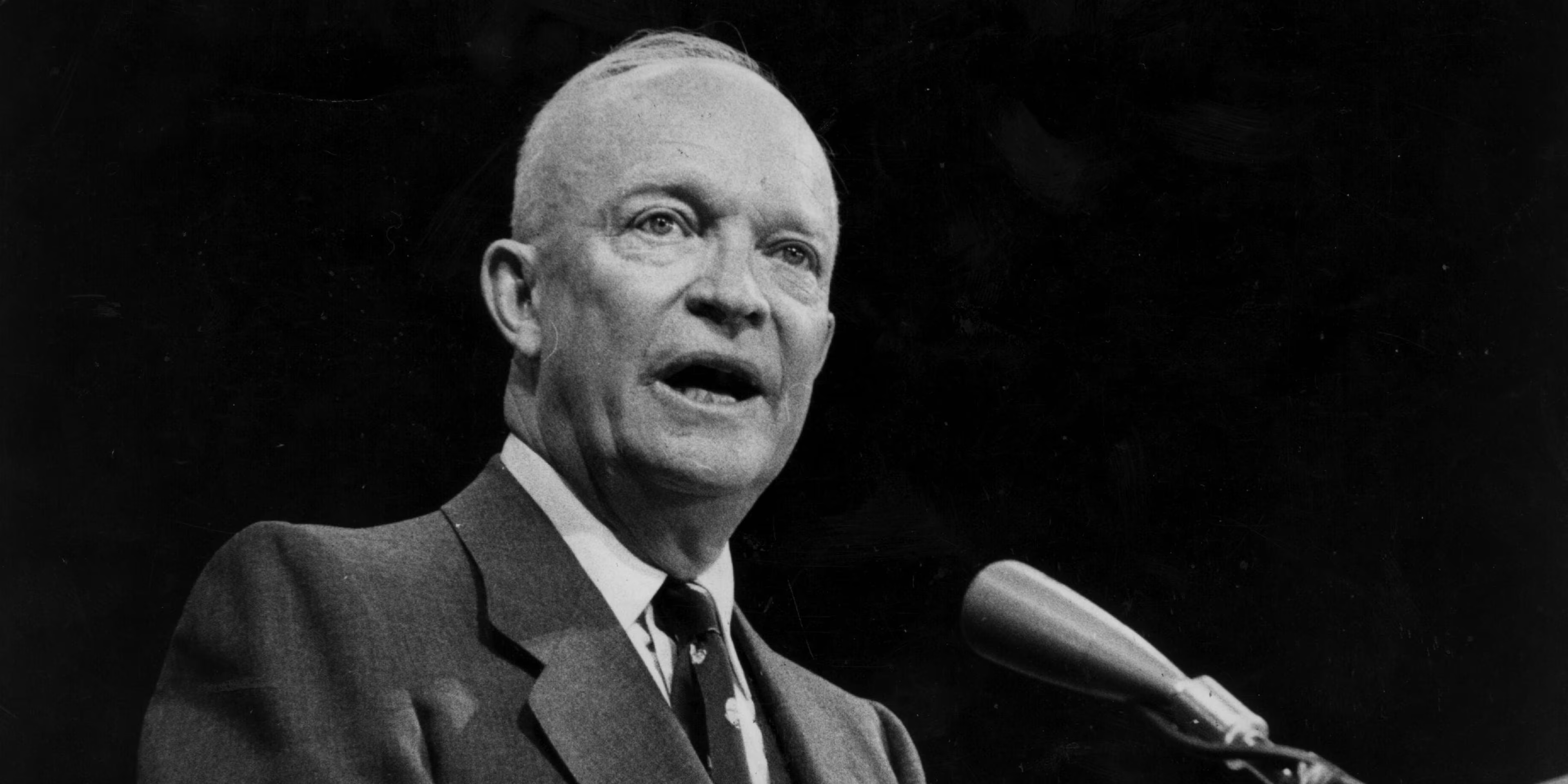

Another speech comes to mind, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s first inaugural, which he delivered in the midst of the Korean War and less than eight years removed from World War II. Near the end he said, “The peace we seek, then, is nothing less than the practice and fulfillment of our whole faith among ourselves and in our dealings with others. This signifies more than the stilling of guns, casing the sorrow of war. More than escape from death, it is a way of life. More than a haven for the weary, it is a hope for the brave.”

Eisenhower was a deeply religious person. His experiences in World War II and then the Cold War deepened his faith. He is the only President to have been baptized in office, at the age of 61 (he was raised in the Mennonite faith, which does not practice baptism). The central tenant of Christianity is overcoming death with the promise of eternal life via Jesus Christ.

Yet arguably Eisenhower was putting country above God, at least in that passage. The key word is “more,” and the key phrase is “More than an escape from death, it is a way of life.” In a sense he inserted the United States of America between people and Christ, setting the country as the source of salvation.

Again, it was hope eclipsing sin: Eisenhower was speaking to a segregated nation in which women and non-Whites were still largely second class citizens. Yet like Lincoln, Eisenhower appealed to the better angels of that wicked land’s nature, that they might lead it once and for all to salvation. Nor were Eisenhower’s words just words. As Lincoln used the presidency to end slavery, he used his power to hasten the demise of the peculiar institution’s progeny, segregation and Jim Crow, not least of all by deploying the National Guard to enforce desegregation in the South.

We haven’t heard much about our better angels from our presidents and leaders this century. I worry about that fact. It’s a reflection of the extent to which many Americans have lost faith in their country. In many ways we’ve been transmogrified from a people that believes in our unique goodness to one obsessed with our unique badness. In some ways we aren’t a people anymore at all, but a Balkanized **** of **** tribes.

On this Memorial Day I chose to revisit the words of Lincoln and Eisenhower (who is, incidentally, in my estimation, the most underappreciated president in U.S. history). Neither man who harbored fantasies or illusions about the country they led. They were intimately aware of its sins. They, each in their own way, helped commit them. But they also believed that the United States of America would one day become the more perfect union the Founders promised. There’s that word again: “more.” Not perfect, but closer to it than any other nation in history.

In the name of wisdom the modern era has installed cynicism in place of hope, as if to believe in our country’s potential is to reveal one a fool, a waif. I could not disagree more vehemently. I think the cynic is the fool, because the cynic has given up. The cynic is the coward no amount of faith can restore. The cynic sees only sin, and bathes in a sort of perpetual self-loathing like a modern day flagellant. Why on earth would I throw in with that lot? Why would any of us?

I believe in the better angels of our nature as Americans, because I see it everyday. I chose to see it. As Lincoln said, ““We can complain because rose bushes have thorns or rejoice because thorn bushes have roses.” I chose to see the men and women who work and fight every day to bring their cities, their states, and their country, a bit closer to their founding ideals. In this relentlessly cynical age, that faith is more important than ever.